(Previously published on LinkedIn and in my newsletter.)

In the LGA’s recently published white paper on the future of local government, there’s a very interesting line about digital. Just the one line, admittedly, but I think it is fair to say that it is doing a lot of work.

We are calling for… [a] Local Government Centre for Digital Technology: using technological innovation to deliver reform and promote inclusive economic growth across councils.

There’s no more detail in the document, and little in the news article about it in UKAuthority either.

Now, I’ve been chatting with Owen Pritchard, who I would guess is the person behind this line, for a few years now, and I don’t doubt that he has his own, very long list of things he thinks the centre should do – so I’m pretty excited to find out in due course what that looks like.

In the meantime though, let me toss around a few ideas… what could this centre do?

1) Coordinate procurement

The first thing for me would be to start investigating how the buying power of the sector could be consolidated to produce economies of scale, and better contracts.

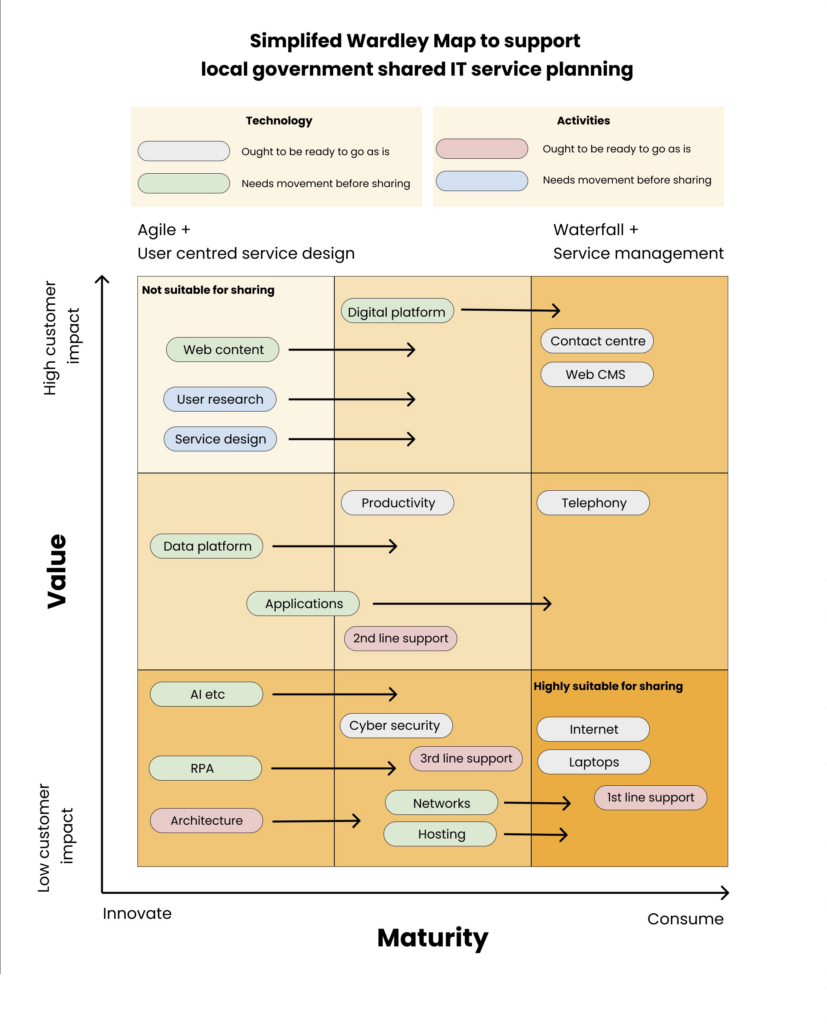

I’d start in the bottom right of a Wardley map, the commoditised digital gubbins that keeps councils running, and where it makes no sense to have that stuff duplicated 300 odd times across the country.

Laptops, phones, broadband connections, hosting services… all these things have councils up and down the country running procurement exercises, negotiating contracts, managing those contracts… all this could be done once nationally, or a few times regionally, with no negative impact on local service delivery.

Once that’s done, how about we move on to using that collective buying power to:

- demand better products from suppliers, particularly in the line of business system market

- consolidate social value across contracts, to create meaningful, large scale opportunities for suppliers to support local public services

- Invest in the development of new products and services, either through existing or new companies, or even local authority trading organisations

This stuff is pretty boring in many ways, but I’m putting it first in this list because I think the actual opportunities are vast.

2) Fill the security gaps

With the cyber assessment framework and the LGA’s own cyber 360 reviews, there is plenty of advice out there in terms of best practice on security. However, many councils are lacking the capacity and the capability to implement this guidance. It’s nobody’s fault, just the result of many small organisations, who through years of austerity have been unable to invest in their technical infrastructure.

This could be sorted by having support available to councils to put in place the measures needed to ensure that data and information is kept as safe as possible from a technical standpoint. Flying squads of security experts who understand the local government environment, are knowledgeable about the frameworks and guidance, and can put in place the necessary steps to make all councils as secure as possible.

3) Education, education, education

One of the most important things that a centre like this could do would be to put a lot of effort into increasing the knowledge of digital across local government. Despite various efforts in recent years, the level of digital confidence within the general workforce in the sector is remarkably low.

We need people in leadership positions to understand what is possible and what they can do to unlock this potential. We need politicians who understand the strategic levers they need to pull to ensure the right long term decisions are being made in councils around technology strategy. We need the specialist teams within local government to be up to speed with the latest developments in cloud, development, security, and data, depending on their role. We need council teams to be way more confident in utilising user-centric service design approaches.

All of this could be advanced really quickly through a properly funded and planned out strategic learning programme across the sector.

The second strand is less about formal training and more about curating existing good practice case studies and examples, and creating ones that don’t exist but really should. Part of the problem of a fragmented sector of over 300 organisations is that it is really hard for anyone to know what is going on everywhere else.

The standard of documenting the good stuff is really poor. Case studies are dominated by vendors, announcing deals and anticipated outcomes, but with no follow up. We have councils going through the process of turning into unitaries, for example, but no documented playbook on how to successfully aggregate the IT in these situations. Why the hell not!? A local government dedicate centre could have a team of researchers and content designers producing useful, findable, actionable content that would help spread the word on how to get things done.

4) Data and standards

Everyone knows about the untapped potential of data within local government, but nobody so far has had the right mix of time, money, and intestinal fortitude to get it done properly.

It means taking on the line of business system providers to open up access to the data; to help navigate the arcane table structures of these creaking software behemoths; to have in place the data platforms to aggregate, transform, and usefully visualise data; to have data engineers and scientists able to formulate the right questions and figure out how to get the answers; and to have service managers who are open and willing to become data informed, and to change a lifetime’s habit of going by hunches and guesswork.

It’s a big ask, and it’s no wonder that progress has been slow. But so many of these problems are shared by every single council in the country. A centre such as the one being propose could come up with a whole host of replicable and scalable answers to these problems.

Alongside this kind of support, there’s also a need for standards around data and a centre could help coordinate and manage standards where they exist, and support the development of them where they are needed. Just as importantly, though, the centre could provide some teeth, ensuring that councils and their suppliers are meeting these standards to enable the safe use of data to improve outcomes for local areas. The use of coordinated, collective buying power would definitely help with this!

Another area of standards where a centre could help would be to produce re-usable data sharing agreements and policy documents, to help councils collaborate with other parts of the local public service system, without the need to reinvent the wheel at significant cost, over and over again.

5) Innovate at scale

Finally, I’d want to see some collective effort at innovating in a coordinated, replicable and scalable way. Pooled resources that can reduce the risk exposure for individual councils, bringing together the best brains and ideas with the people best at delivering results, to experiment, test, iterate and improve on radical ideas for local public services.

It’s far too big a risk for individual councils to take on, and no surprise that transformational change in local government is often so incremental. The exploration of new operating models in the internet era – companies like Uber, AirBnB, Netflix and so on – have been funded by billions in venture capital. But somehow we expect councils do be able to do it, alongside running the existing services, on a shoestring?

Imagine a centre, with enough resources to be able to pull together the best service design folk, the best data people, the best technologists, the subject matter experts for specific services, all able to identify the biggest challenges facing the sector and to innovate their way through to workable solutions that can be adopted across the sector. With this kind of scale and authority, such a centre could have the clout to agitate for legislative reform where it is needed, to call for the establishment of new institutions to deliver specific outcomes, or to work alongside existing council teams to help them adopt the new models.

There’s 5 ideas I had. Any thoughts?